Pilgrimage: ‘an outward enactment of an inward journey.’ In some religions, specific pilgrimages are mandatory. In others, they are not. In this essay, I take a brief look at pilgrimages in Hinduism.

Pilgrimage

As the definition above states, it is a symbolic action. It has various kinds of meanings for the individual pilgrim. ‘Pilgrim’ and ‘pilgrimage’ come to us from the Latin peregre meaning ‘through (i.e., beyond the borders of the) field’ (source: dictionary.com). The ‘field’ here means ‘area’, with a geographic meaning. Thus, it is someone who traverses a field outside.

In Hinduism, a pilgrimage has several components. In general, they are something like this:

- Sankalpa – resolve, resolution. This is the resolution that ‘I shall undertake a pilgrimage.’

- Preparation – undertaking various actions to develop the attitude of devoutness for the pilgrimage. Examples: abstaining from certain kinds of foods, performing daily rituals (symbolic acts), prayer, etc. These help prepare the mind for the whole pilgrimage.

- Yaatraa – this is the pilgrim’s actual movement (journey) to the shrine(s). This is the ‘sacred trace’, a sacred journey. Even now, people believe that the more difficult the sacred (i.e., the more arduous) journey is, the more sacred, meritorious, and rewarding it will be. Hence, pilgrims going on foot are considered the most devout; more so, if the feet are bare.

- Hierophany – a sacred experience. The result of participation in sacred rituals and the darshana (beholding the divine) at the sacred place (shrine). This can take many forms, e.g.: peace, joy, spiritual ecstasy etc. It varies from individual to individual.

- Transformation – the hierophany at the sacred place is expected to lead the pilgrim to become a better person; kinder, gentler, stronger, ethical, spiritual, etc.

- Return – The pilgrims return transformed and carries a bit of the sacred place they visited, and their experience there, within themselves. These influence their conduct and their lives become better. They spread these transformations in the geographical space they occupy through their interactions with others.

A pilgrimage must result in a transformation of the pilgrim into a better social being. This has far-reaching geographical meaning.

Impact

Quite often, returning pilgrims bring with them sacred objects: consumable items (sacred water, rock candy, the sweet preparation called panchaamritam, sacred ash or vibhuti, turmeric, kumkuma, sandal paste, etc.) or non-consumable items (sacred figurines, beads, flowers, etc.). These are the ‘souvenirs’ of their visit to the shrine.

Thus, the receiver of these gifts is getting a symbol of the sacred place and it sacred ‘vibes.’

Remember, sacred journeys need not be just about religion. I have known people who carry a pebble or small amount of soil, etc. from places they visit and gift them to those who did not go with them.

It’s about place and a sacred experience of it, even if no ‘religion’ is involved.

The returning pilgrim, transformed by the sacred experience (hierophany) shares a little of that experience through objects and through their life. This is important because a person at peace does not do bad unto others.

Therefore, this transformation is spread in geography. If this is achieved, then, the idea of the rg-veda is achieved: For the liberation of oneself, and for the good of the world. Thus, the pilgrim, by his geographical enactment of his inward spiritual journey attains (at least some measure of) peace and uses that for the good of the world. This is a classic case of what geographers call ‘contagious diffusion’ – spreading of ideas through personal contact.

Organization

In Hinduism, pilgrimage is largely (almost entirely) what my guru, Dr Surinder Mohan Bhardwaj, calls a self-organizing system – there is no authority that says that any particular pilgrimage should be performed. Diverse belief systems within what is called Hinduism have their own pilgrimages based on their individual beliefs.

No one is required to participate. And when people do participate, they may participate in a variety of different ways. Here are some examples:

Varkari – this is an annual pilgrimage to Pandharpur, Maharashtra. Large numbers of pilgrims from many different places walk to Pandharpur to have darshana of the deity. Along the route, they sing sacred songs, dance, narrate sacred stories, etc. Those who cannot go on the pilgrimage participate through voluntary service to help those who are going. One of the most visible things is how temporary roadside facilities are set up to offer food, water, and rest areas for pilgrims. In this pilgrimage, social hierarchies are largely set aside. My friend Sunil Ganu who lives in Pune tells me that Ms Lakshmibai, who cooks for him, volunteers to cook for the varkari pilgrims as they pass through Pune. She’s not exactly wealthy! Yet, she sees it as her sacred contribution to the varkari – this is how she participates.

Sabarimalai – this is another classic example of a self-organizing phenomenon. Traditionally, the pilgrim is supposed to undergo some forty days of austerities, dressing in black, cooking their own food, participating in daily worship, etc. and join a pilgrim group.

Kumbha mela – this is the largest self-organized pilgrimage in the world, involving over a million pilgrims each year (128 million estimated for 2018).

Explore:

- Find out about pilgrimages in different parts of the world and in different religions, especially those of your friends.

- If you have yourself gone on a pilgrimage, reflect and write about the geography concepts in that experience.

- If you wish to go on a pilgrimage, what would be the steps you would undertake (look at the list in this essay)?

- How does pilgrimage affect non-sacred activities such as economic activities at the sacred place and on the sacred routes?

- What are different ways in which one may participate in a pilgrimage?

Join us for the 6th International Geography Youth Summit, IGYS-2020,

24-26 July 2020, Bengaluru

A version of this article appeared in the Deccan Herald Student Edition on 18 September 2019

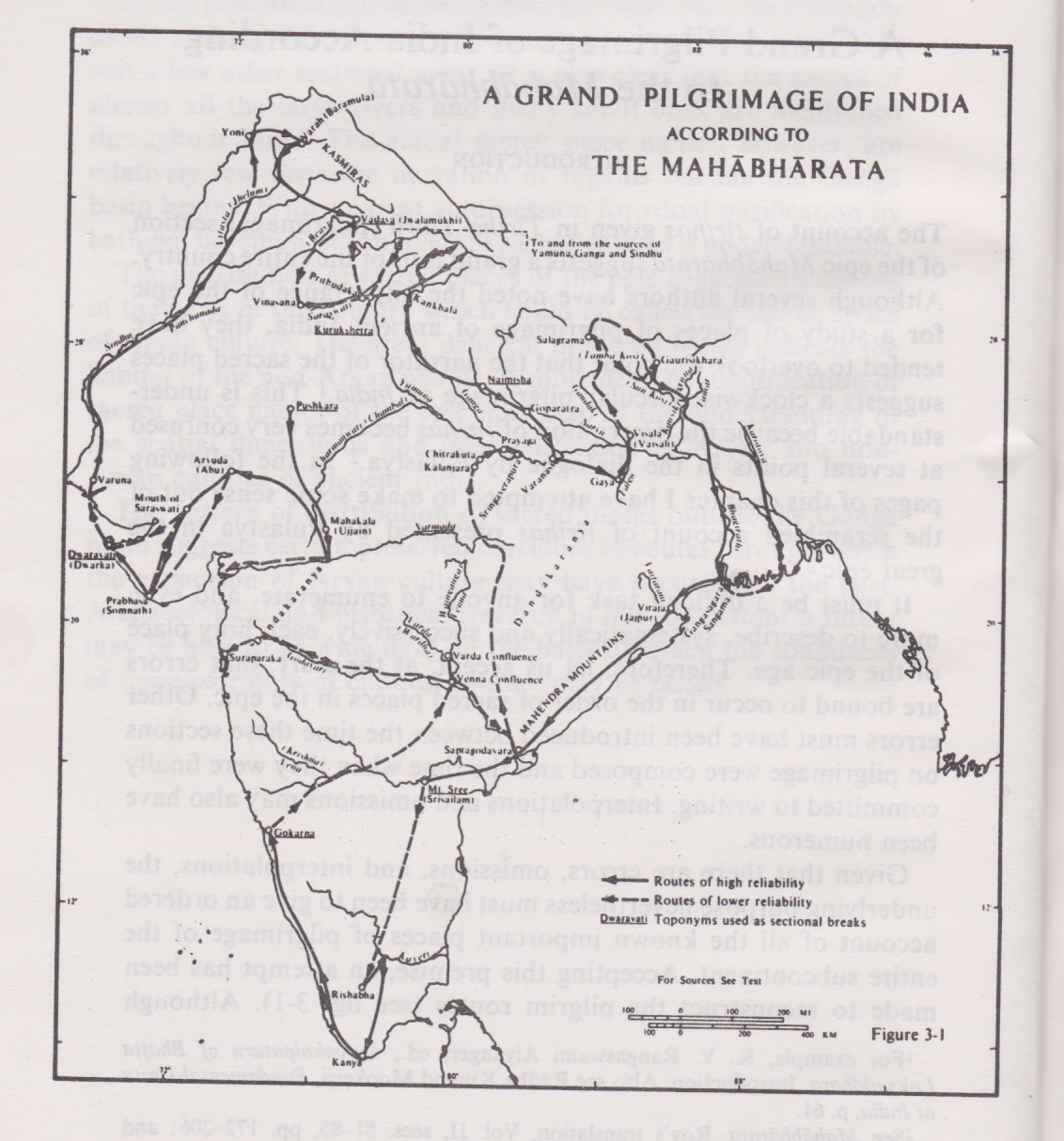

Featured image: Pilgrimage places mentioned in the Mahābhārata: an ancient geography of India. [Source: Surinder Mohan Bhardwaj (2003) Hindu Places of Pilgrimage in India.] (Courtesy, Munshiram Mohanlal Publishers).

No responses yet